Transitions and Transformations (1980–1984)

Disco did not disappear at the dawn of the 1980s. It transformed. As the genre’s commercial peak faded and its mainstream visibility waned, the musical experimentation and underground energy intensified. What emerged was a dazzling array of new directions – leaner grooves, funkier edges, and pioneering sounds that would shape the next two decades of dance music.

The voices remained at the core. Singers who had thrived in the disco era either adapted or deepened their styles. Evelyn “Champagne” King moved from lush disco arrangements to stripped-down boogie, while Diana Ross embraced icy synth textures in tracks like “Swept Away.” Whitney Houston would soon emerge, trained in gospel but shaped by the polished dance-pop production of Narada Michael Walden and Kashif under the strategic vision of Clive Davis. Vocal performances in this era became more dynamic and rhythmic – less operatic, more urgent – blending the emotional depth of soul with the swagger of modern funk.

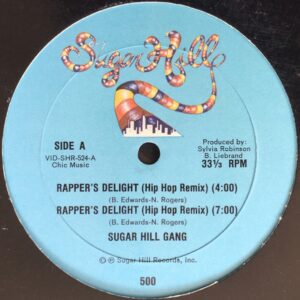

Rapper’s Delight” — The birth of hip-hop, brought to life by visionary producer Sylvia Robinson / Source: discogs.com

Instrumentalists and session musicians, often the unsung heroes of the 1970s, gained new visibility. Bassists like Louis Johnson (The Brothers Johnson), keyboardists like Greg Phillinganes (who worked with Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, and Quincy Jones), and drummers like James Gadson (who played on classic tracks by Bill Withers, Marvin Gaye, and Diana Ross) carried the groove with precision and creativity. Their presence was felt on countless recordings, where tight rhythm sections met shimmering synth lines and sharp guitar licks. These players brought continuity from the disco era into the new sound, often supporting emerging solo stars and shaping R&B’s rhythmic future.

Producers became central architects of this evolution. Quincy Jones created genre-blending masterpieces like “Thriller” for Michael Jackson, mixing pop, funk, disco, and rock into a sonic juggernaut. Narada Michael Walden crafted hits for artists like Whitney Houston and Aretha Franklin. Kashif produced Evelyn “Champagne” King and Howard Johnson with slick, synth-forward flair. The Bee Gees, now seen more as songwriters and studio innovators than pop idols, wrote for Barbra Streisand and Dionne Warwick. ABBA’s Benny and Björn continued experimenting with layered vocals and digital recording, pushing Europop toward dance-pop’s future. These producers modernized disco’s foundations – less strings and orchestration, more electronic polish and cross-genre daring.

The instrumentation also evolved. Gone were the full orchestras and horn sections of the Philly sound. In their place came Yamaha DX7s, Roland TR-808 drum machines, slap bass, and minimalist synth stabs. The groove remained, but it was redefined: more space, more bounce, more funk. The basslines of boogie – a subgenre that bridged disco and R&B – became rubbery and rhythmic, as heard in Shalamar’s “I Can Make You Feel Good” and Yarbrough & Peoples’ “Don’t Stop the Music.” Meanwhile, electro began to flirt with robotic textures, as in Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock,” fusing hip hop with Kraftwerk-like precision.

Technological innovation drove much of this change. Portable four-track recorders and MIDI allowed for leaner production and more independent workflows. The Linn LM-1 Drum Computer brought digital precision to rhythm, using real drum samples instead of analog synthesis, for layering textures. Its crisp, punchy sound shaped hits by Prince, Michael Jackson, Human League and countless early ’80s icons – setting a new standard for groove in the post-disco era. ltering how rhythm could sound. The 12-inch single format, though born in the disco era, remained crucial – providing extended grooves for club play and remix culture.

Among the most pivotal moments was the release of Rapper’s Delight by the Sugarhill Gang — widely recognized as the first commercially successful hip-hop record. Though released just before the new decade, its influence boomed into the early ’80s, signaling how disco’s rhythmic base could birth new genres like hip hop. Behind it stood Sylvia Robinson, co-founder of Sugar Hill Records, whose vision saw beyond disco’s decline. A former disco singer herself (“Pillow Talk,” 1973), Robinson recognized the raw energy of the emerging street sound and became one of the first to professionally produce and promote hip-hop artists. Through Sugar Hill Records, she continued to work with pioneering acts like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, The Sequence, and Treacherous Three, turning a local movement into a cultural revolution. In a male-dominated industry, Robinson carved out space helping to shape the emerging hip hop movement with the same dancefloor instincts that once drove disco.

“We didn’t stop dancing – we just found new ways to move.”

— Frankie Knuckles, Chicago, 1983

By 1984, new genres were crystallizing. Boogie had defined post-disco’s funkier side. Electro was charting a futuristic path. Early house music had just begun to emerge in Chicago basements, notably with Jesse Saunders’ “On and On.” These sounds still pulsed with disco’s heartbeat – a steady 4/4 rhythm, an emphasis on movement, and a belief in dance as both joy and resistance.

Disco wasn’t fading. It was decentralizing. The mainstream spotlight moved on, but the underground kept spinning, producing, innovating. A new chapter was coming – and disco’s DNA would be at its core.

CONTINUE EXPLORING DISCO’S MUSICAL BLUEPRINT:

• Origins of the Sound (1972–1979)

• Beyond the Mirrorball (1985-2005)

• Disco Goes Digital (2006-today)

SOUND REFLECTIONS:

A few tracks that captured the evolving spirit of disco between 1980 and 1984, where funk met future, and dance music took bold new forms:

-

-

Change – “A Lover’s Holiday” (1980)

A breezy blend of post-disco groove and soulful optimism, this track bridged the elegance of the ’70s with the tighter polish of the ’80s. -

The S.O.S. Band – “Just Be Good to Me” (1983)

Produced by Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis, this song introduced a sleek, electronic funk sound that would soon dominate R&B and pop. -

Evelyn “Champagne” King – “Love Come Down” (1982)

Driven by a fat synth bassline and King’s radiant vocal, this track defined the clean, synth-forward direction of early-’80s club music. -

D-Train – “You’re the One for Me” (1981)

An explosive fusion of boogie, gospel energy, and electronic rhythm, this anthem marked the rise of dancefloor intensity with emotional weight. -

Shannon – “Let the Music Play” (1983)

A defining freestyle track that introduced a new syncopated club beat, fusing Latin rhythm with electronic drama. -

BB&Q Band – “On the Beat” (1981)

This quintessential post-disco groove delivered a punchy rhythm section and glossy production, perfect for the roller disco era. -

Klein & MBO – “Dirty Talk” (1982)

A bold Italo-disco cut with mechanical drive and provocative flair – its raw electronics hinted at techno and house to come. -

Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five – “The Message” (1982)

Built on a funk-disco foundation, this track shifted focus to lyrical realism – a game-changer that proved dance music could carry hard truths. -

Sylvester – “Do Ya Wanna Funk” (1982)

Teaming up with Patrick Cowley, Sylvester took disco into the Hi-NRG stratosphere – euphoric, sensual, and defiantly proud. -

Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force – “Planet Rock” (1982)

A futuristic blend of Kraftwerk-inspired electro and Bronx street energy, this record signaled the genre-blurring future of global dance music. -

Patrick Cowley – “Menergy” (1981)

An underground classic that pushed sexual liberation and sonic experimentation to the forefront of club culture.

From shimmering synths to early rap verses, these tracks don’t just mark a moment – they echo the creative explosion that followed disco’s first wave.

Full Spotify playlist: TOP 300 ESSENTIAL POST-DISCO CLASSICS (1980-1984)

-